Significance of the Jewel Tower

The Jewel Tower is important principally as a rare survival of the medieval Palace of Westminster, with much of its 14th-century architecture remaining relatively unaltered. In its 650-year history the tower has served three significant functions related to the government of England.

Survival

The Jewel Tower is one of the few surviving buildings of the medieval Palace of Westminster, the central residence of the English monarchy for much of the Middle Ages. Only three other buildings – Westminster Hall, the chapel of St Mary Undercroft, and St Stephen’s Cloister – survived the fire of 1834 and the construction of the present Palace of Westminster. Of these, the chapel and the cloister may only be visited by special arrangement.

Successive Uses

The Jewel Tower has strong associations with three successive functions: the royal keeping of jewels and plate (from the building's construction in the 1360s to the early 16th century), the storage of the records of the House of Lords (from the late 16th century to 1864), and the Weights and Measures office between 1869 and 1938.

Though it is the first of these that has most caught the public imagination, assisted by the name ‘Jewel Tower’ – apparently first coined in the 19th century[1] – the second use has arguably been of greater significance, through the safeguarding of documents central to the nation’s ‘memory’. Physical changes to adapt the building better for this purpose have transformed the tower's exterior and all spaces of the interior.

The Weights and Measures office, though comparatively short-lived and involving no great alterations to the tower’s fabric, nevertheless made decisions whose repercussions were felt throughout the British Empire.

Taken as a whole, the history of the Jewel Tower embodies the evolution of the state from a monarchy (limited to England) to a Parliamentary democracy (the United Kingdom) and, in the 19th and 20th centuries, to an imperial power.

Building Type

The Jewel Tower is a good example, surviving in a relatively unaltered condition, of a medieval treasury. Treasuries could serve institutions such as colleges, guilds, civic corporations, parish churches and cathedral chapters, and powerful individuals. Although a number of examples survive in England, little dedicated study has been carried out on them as a class.

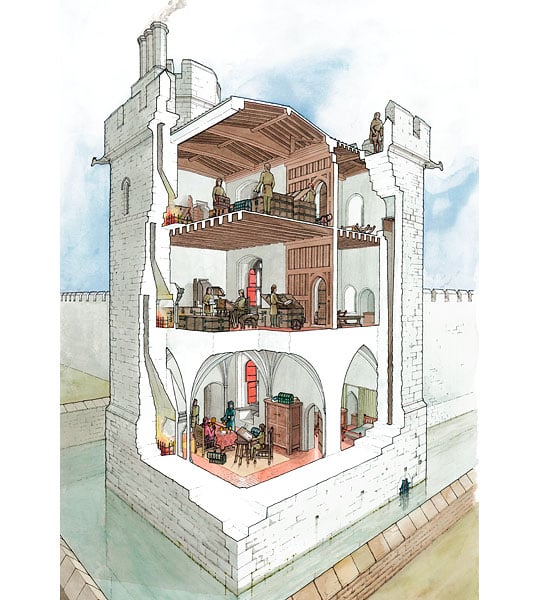

The Jewel Tower’s fabric does allow certain general observations about concerns for security, in features such as the attached walls and moat, the original pattern of fenestration (with no windows on the ground floor facing outside the palace enclosure, and only two small windows on the first floor), and the evidence for double doors at the entrance to the uppermost floor. This level was clearly intended to contain particularly sensitive or valuable items.

Architecture

The tierceron vault and sculpted bosses over the main room on the ground floor attest to a high standard in the original design for the building. This is to be expected of a royal building, and accords with perceptions of its master mason Henry Yevele (d.1400) and master carpenter Hugh Herland (d. c.1406) as craftsmen pre-eminent in their day.

Most of the other medieval architectural features of the building (the windows, main door and parapet) have been defaced or removed through later changes. Given the near-certainty that the tower was intended from the outset as a secure repository for the king’s goods, it is likely that its original architectural character was functional rather than ostentatious.

The 18th-century Portland stone windows, under three-centred arches, and particularly the small windows in the stair turret, make a strong contribution to the appearance of the Jewel Tower. The distinctive shape of the latter windows strongly suggests that the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor (d. 1736) took an active role in designing the new features, as they are paralleled by windows he designed elsewhere.

International Recognition

Since 1987 the Jewel Tower has formed part of the Westminster World Heritage site, together with the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey.

Footnote

1. In the Middle Ages, the building was denoted by a number of topographical terms, but usually by the name ‘Jewel House’. From 1600 the convention was to speak of the complex in which the tower stood as the ‘Parliament Office’, with the tower occasionally being specified as the ‘Stone Tower’ or even ‘Tower of White Stone’. The exact process by which the memory of the tower's first function was retained or revived is not presently known, but clearly by the mid-19th century there was some appreciation of this, albeit with numerous inaccurate details concerning the ‘Crown Jewels’.