1. Witches were burned at the stake

Not in English-speaking countries. Witchcraft was a felony in both England and its American colonies, and therefore witches were hanged, not burned. However, witches’ bodies were burned in Scotland, though they were strangled to death first.

2. Nine million witches died in the years of the witch persecutions

About 30,000–60,000 people were executed in the whole of the main era of witchcraft persecutions, from the 1427–36 witch-hunts in Savoy (in the western Alps) to the execution of Anna Goldi in the Swiss canton of Glarus in 1782. These figures include estimates for cases where no records exist.

3. Once accused, a witch had no chance of proving her innocence

Only 25 per cent of those tried across the period in England were found guilty and executed.

4. Millions of innocent people were rounded up on suspicion of witchcraft

The total number of people tried for witchcraft in England throughout the period of persecution was no more than 2,000. Most judges and many jurymen were highly sceptical about the existence of magical powers, seeing the whole thing as a huge con trick by fraudsters. Many others knew that old women could be persecuted by their neighbours for no reason other than that they weren’t very attractive.

5. The Spanish Inquisition and the Catholic Church instigated the witch trials

All four of the major western Christian denominations (the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist and Anglican churches) persecuted witches to some degree. Eastern Christian, or Orthodox, churches carried out almost no witch-hunting. In England, Scotland, Scandinavia and Geneva, witch trials were carried out by Protestant states. The Spanish Inquisition executed only two witches in total.

6. King James I was terrified of witches and was responsible for their hunting and execution

More accused witches were executed in the last decade of Elizabeth I’s reign (1558–1603) than under her successor, James I (1603–25).

The first Witchcraft Act was passed under Henry VIII, in 1542, and made all pact witchcraft (in which a deal is made with the Devil) or summoning of spirits a capital crime. The 1604 Witchcraft Act under James could be described as a reversion to that status quo rather than an innovation.

In Scotland, where he had ruled as James VI since 1587, James had personally intervened in the 1590 trial of the North Berwick witches, who were accused of attempting to kill him. He wrote the treatise Daemonologie, published in 1597. However, when King of England, James spent some time exposing fraudulent cases of demonic possession, rather than finding and prosecuting witches.

7. Witch-hunting was really women-hunting, since most witches were women

In England the majority of those accused were women. In other countries, including some of the Scandinavian countries, men were in a slight majority. Even in England, the idea of a male witch was perfectly feasible. Across Europe, in the years of witch persecution around 6,000 men – 10 to 15 per cent of the total – were executed for witchcraft.

In England, most of the accusers and those making written complaints against witches were women.

8. Witches were really goddess-worshipping herbalist midwives

Nobody was goddess-worshipping during the period of the witch-hunts, or if they were, they have left no trace in the historical records. Despite the beliefs of lawyers, historians and politicians (such as Karl Ernst Jarcke, Franz-Josef Mone, Jules Michelet, Margaret Murray and Heinrich Himmler among others), there was no ‘real’ pagan witchcraft. There was some residual paganism in a very few trials.

The idea that those accused of witchcraft were midwives or herbalists, and especially that they were midwives possessed of feminine expertise that threatened male authority, is a myth. Midwives were rarely accused. Instead, they were more likely to work side by side with the accusers to help them to identify witch marks. These were marks on the body believed to indicate that an individual was a witch (not to be confused with the marks scratched or carved on buildings to ward off witches).

Diane Purkiss is Professor of English Literature at Keble College, University of Oxford

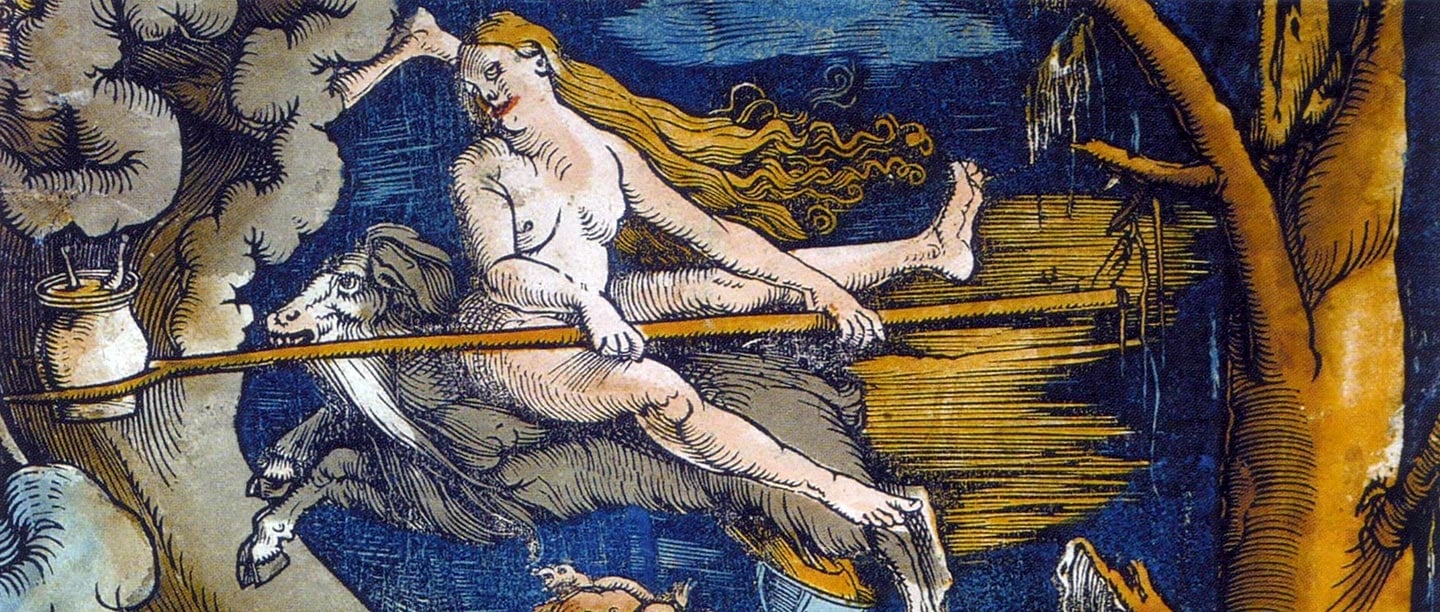

Top image: Detail from ‘Witches’, a 1508 painting depicting the Witches’ Sabbath

(©Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Explore more

-

English Heritage Histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

-

Women in history

Read about the remarkable lives of some of the women who have left their mark on society and shaped our way of life – from Anglo-Saxon times to the 20th century.

-

A Journey into Witchcraft Beliefs

Step into the world of early modern England as Professor Diane Purkiss describes popular and intellectual beliefs about witchcraft in the 16th and 17th centuries.