Parliamentary Reform

The campaign for women’s suffrage was part of wider legislative struggles to enfranchise new groups of voters in Britain during the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 1832, the Representation of the People Act (known as the First Reform Act) was passed. This introduced a number of parliamentary reforms, including extending the right to vote in parliamentary elections to more men (through various property qualifications). However, the act defined a voter as male and therefore formally excluded women from voting.

Over the next decades, numerous Reform Acts were passed which extended the franchise to certain groups, but women would have to wait almost a century before it would be extended to them.

Early Years

The formal women’s suffrage campaign began in the 1860s. John Stuart Mill was elected as MP for Westminster in 1865, and was the first candidate to include women’s suffrage in his election address to voters. In the same year, the Kensington Society was established, a debating society for women which discussed issues on the position of women, such as property rights, education and parliamentary reform.

In 1866, the Kensington Society formed an informal committee to draft a petition, led by women such as Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett. This was the first mass women’s suffrage petition. It argued for all householders who met the property or rental qualification, regardless of sex, to have the vote. Signed by around 1,500 women, it was presented by Mill to the House of Commons on 7 June 1866.

A year later, Mill also proposed an amendment to the Second Reform Act, asking for the term ‘man’ to be replaced with ‘person’, so as to include women householders. While the amendment was rejected, the petition and proposed amendment mobilised those interested in women’s suffrage.

The Kensington Society was dissolved in 1868 and was superseded by the early suffrage societies, such as the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS) which formed in 1867. This was a loose federation of local suffrage societies including London, Edinburgh and Manchester.

The Suffragists

By 1888, the NSWS had split in two and was succeeded by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) which formed in 1897. Led by Millicent Fawcett, the NUWSS believed in achieving women’s suffrage through constitutional means. The term suffragist is often associated with the NUWSS, and refers to suffrage supporters who used peaceful methods to campaign.

This included lobbying and petitioning MPs, organising marches, and holding public meetings. The NUWSS also published its own journal, The Common Cause and distributed educational propaganda. By 1913, the NUWSS had almost 500 regional suffrage societies affiliated to it and a total membership of 50,000.

The NUWSS organised the first large-scale women’s procession in 1907. Around 3,000 women marched through London in the rain to raise awareness for a private members’ bill on women’s suffrage. Due to the wet conditions, it became known as the ‘mud march’.

Those involved in women’s suffrage came from a range of backgrounds, but it was more common for individuals to be middle or upper class.

The Suffragettes

By the beginning of the 20th century, some within the movement became frustrated at the NUWSS’s lack of progress. In 1903, at the home of Emmeline Pankhurst in Manchester, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was established. Emmeline’s three daughters, Christabel, Sylvia and Adela, were also involved in its formation.

Known for their motto ‘Deeds not Words’, the WSPU used militant tactics such as heckling MPs, stone-throwing, window-smashing, damaging landmarks and works of art, and arson attacks. While they also used more traditional methods such as holding mass meetings and organising petitions, their extreme tactics gained national attention.

The WSPU became associated with the term suffragette – referring to campaigners who used militant methods. Over 1,000 women were arrested for their militant acts. Many went on hunger strike in prison, as they were not given the status of political prisoners. This resulted in the government introducing force-feeding.

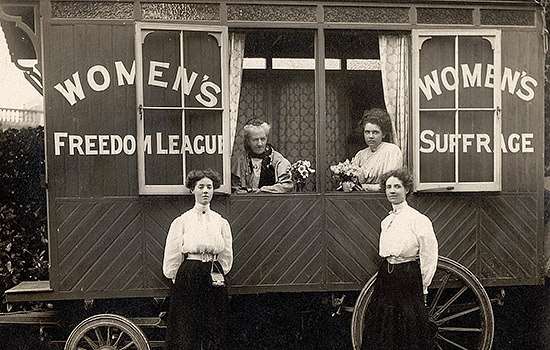

In 1907, disagreements over the WSPU’s increasingly autocratic style of leadership led to a breakaway group forming called the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). While still a militant organisation, it used direct action, such as census boycotts and passive resistance to taxation, and was non-violent in its approach.

Other organisations that campaigned for women’s suffrage included those grounded in professional identities, such as the Actresses’ Franchise League and the Artists’ Suffrage League. Women often had multiple memberships and belonged to several organisations. Many men also supported the cause, and in 1907 the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage was formed.

The First World War

Many suffrage organisations suspended their activities during the First World War (1914–18) and focused on supporting the war effort. The WSPU leadership ended its militant campaigning and Emmeline Pankhurst assisted the government to recruit women into war work. While the NUWSS remained committed to women’s suffrage, it concentrated its efforts on relief work. As some suffrage campaigners held pacifist views, this led to them leaving these organisations.

Yet the campaign for women’s suffrage did not stop altogether. The WFL suspended its direct-action methods, but continued to organise petitions and deputations to Parliament. Disgruntled WSPU members also established two new organisations – the Suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union, and the Independent Women’s Social and Political Union, which continued to campaign for women’s voting rights.

During the war, many women worked in industries previously reserved for men, such as transport, agriculture and munitions manufacturing, and many served in the newly formed auxiliary services. This proved that women were capable of working in jobs traditionally seen as ‘masculine’ – helping to change society’s perceptions of the role of women and strengthen the case for women’s right to vote.

Taking to the Polls

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act was passed, which granted the right to vote to women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification, and all men over the age of 21. The act enfranchised around 8.5 million women who made up 40% of the electorate. In December, women took to the polls for the first time in the 1918 General Election. There was great interest in how the female electorate would impact the election, and parties across the political spectrum appealed to women voters.

While this act represented a significant milestone, women did not have the vote on the same terms as men. Indeed, many women who had campaigned tirelessly for the vote remained excluded. So the struggle for equal franchise continued.

The Fight for Equal Terms

After 1918, the campaign for equal franchise became part of a wider programme within the interwar women’s movement. The pre-war suffrage societies evolved and new organisations were formed. In 1917, the WSPU relaunched as the Women’s Party, a political party appealing to women, although it had folded by 1919.

The NUWSS began to campaign on a broader agenda. In 1919, it changed its name to the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC) and Eleanor Rathbone succeeded Fawcett as its president. Equal franchise remained a central issue, but the NUSEC also campaigned on other inequalities affecting women, including the opening up of the professions and equal guardianship over children. The NUSEC’s methods remained largely the same, although from 1918 it also supported numerous women parliamentary candidates. The WFL continued to function much as it had before, and remained committed to securing equal franchise.

In 1921, the Six Point Group was established by Lady Rhondda and published its own magazine called Time and Tide. While it initially campaigned on six specific points, these later evolved into six general points of equality for women: political, occupational, moral, social, economic and legal.

Outside these non-party feminist organisations, many women were also active members of political parties and advocated for equal franchise through existing party structures. Women MPs elected in this period largely supported equal franchise too.

Equal Franchise Act 1928

In 1928, the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act was passed, which removed the age and property restrictions on women’s voting rights. Women could now vote on the same terms as men, from the age of 21. Many suffrage campaigners watched the Equal Franchise Act receive Royal Assent in the House of Lords chamber.

The act represented decades of campaigning by tens of thousands of suffrage supporters, and increased the female electorate to 15 million. For the first time, women became the majority of the electorate, making up 52.7% of voters.

By Dr Lisa Berry-Waite, Historian and Heritage Professional, UK Parliament’s Heritage Collections

Explore more

-

Women who made History

Read about the remarkable lives of some of the women who have left their mark on society and shaped our way of life.

-

The Women’s Freedom League

The Women’s Freedom League was a suffragist and equal rights campaigning organisation. It had its former headquarters at 1 Robert Street, Strand, which is marked with an English Heritage blue plaque.

-

The NUWSS

Learn more about the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), commemorated with a blue plaque at 22 Great Smith Street, Westminster – its headquarters from 1910 to 1918.

-

Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel led the militant campaign for women’s right to vote in the early 20th century. A blue plaque commemorates the home they shared during the First World War.

-

Sylvia Pankhurst

Sylvia Pankhurst was a political activist and campaigner for women’s rights, who is remembered chiefly for her use of militant tactics in the fight for women’s right to vote.

-

Emily Wilding Davison

Emily Wilding Davison, teacher and suffragette, campaigned boldly and tirelessly for women’s rights, even paying the ultimate price for her dedication to the cause.

-

Millicent Garrett Fawcett

Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett was the leader of the peaceful campaign for women’s suffrage. A blue plaque marks the home where in 1928 she saw women finally achieve equal voting rights.

-

Mary Middleton: On Campaign

Read about Mary Middleton, one of the early women candidates for Parliament, the challenges she faced and the legacy of the first women to stand for Parliament.