LABOUCHERE, Henry (1831–1912)

Plaque erected in 2000 by English Heritage at Radnor House, Pope’s Villa, 19 Cross Deep, Twickenham, TW1 4QG, London Borough of Richmond Upon Thames

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Politician, Journalist

Category

Politics and Administration

Inscription

HENRY LABOUCHERE 1831–1912 Radical MP and Journalist lived here 1881–1903

Material

Ceramic

Henry Labouchere was a radical Member of Parliament and a journalist, who is notorious today for having proposed the clause in the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 that was used in many prosecutions of gay men.

Campaigning journalist

Born in London to a family of Huguenot origin, Henry Du Pré Labouchere was the heir to a banking fortune, and had stints as a diplomat and as a theatrical impresario before making his name as a successful journalist. He reported from besieged Paris in 1870 and wrote for papers such as the Daily News before founding Truth in 1877. This journal mixed exposés of establishment corruption and hypocrisy with society gossip.

Labouchere opposed British imperialism, including the Boer War. He frequently denounced ‘“Rule Britannia” nonsense’ and demanded an enquiry into the actions of Cecil Rhodes. A poem by Labouchere, entitled ‘The Brown Man’s Burden’ (1899) – a riposte to ‘The White Man’s Burden’ by Rudyard Kipling – contains the lines:

Pile on the brown man’s burden,

And if his cry be sore,

That surely need not irk you--

Ye’ve driven slaves before.

Seize on his ports and pastures,

The fields his people tread;

Go make from them your living,

And mark them with his dead.

However, Labouchere’s campaigns in Truth became increasingly anti-Semitic, particularly in their negative associations of Jewish people with monopoly capitalism. One article has noted that the virulence of Labouchere’s anti-Semitism was close to that found more commonly in continental Europe.

Radical Member of Parliament

Labouchere was elected to Parliament in 1880 as a Liberal MP for Northampton and stood down in 1906 following his implication in a financial scandal. He never became a minister, partly because of Queen Victoria’s hostility – Labouchere, who had republican leanings, once suggested she should sell one of her palaces to pay for the upkeep of her family.

In Parliament ‘Labby’ gained a reputation as an impressive orator. He supported home rule for Ireland and was strongly opposed to women’s suffrage. In his personal life, he was a keen gambler, once fought a duel in Sweden and frequented brothels. But despite his own apparently libertine and libertarian lifestyle, Labouchere’s lasting political legacy was his introduction of a piece of legislation that would be used to persecute gay men for years to come.

The Labouchere amendment

On 6 August 1885 Labouchere proposed an amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment bill, which was intended to tighten the laws on female prostitution for the protection of women and girls.

His clause expressly made ‘gross indecency’ between men a crime punishable by up to two years in prison, with or without hard labour. Labouchere proposed a penalty of a single year, but agreed to the former Attorney-General’s suggestion that this should be doubled. Later, in the wake of Oscar Wilde’s trial, he made a doubtful claim that he had originally wanted a seven-year maximum sentence, but that government ministers had talked him out of it.

In his introduction to the amendment – which he later said was based on the French criminal code – Labouchere observed that under current law men could only be prosecuted for an ‘assault’ on a boy under the age of 13, and his objective was ‘to make the law applicable to any person’. The implicit characterisation of all male-to-male sex as assaults is offensive today, but would not have been considered so at that time, and the new clause passed without debate.

It should be noted that ‘buggery’ was already illegal, and punishable with a life term, as indeed – despite what Labouchere said – was ‘any indecent assault upon a male person’, by the terms of an 1861 Act, and punishable by up to ten years in prison. However, the vagueness of Labouchere’s amendment about what constituted ‘gross indecency’, and the silence on proof required, led to a big rise in the number of prosecutions, and the amendment became a blackmailer’s charter.

Labouchere’s amendment was used to prosecute, among many others, Oscar Wilde (for whom he had once expressed admiration) in 1895, Alan Turing in 1952 and John Gielgud the following year. It became an enabler for a climate of fear, and of practices such as the police entrapment that caught Gielgud. Male homosexuality was partially decriminalised in England in 1967.

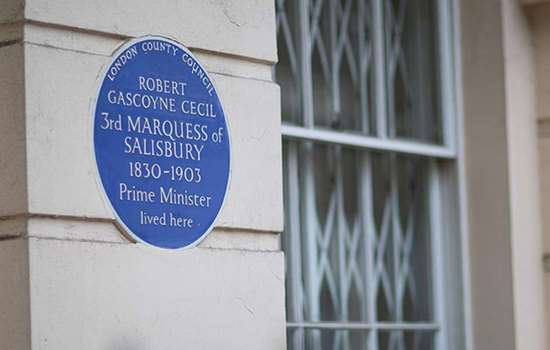

Blue Plaque

When Labouchere’s blue plaque was agreed by the awarding panel, it is not clear that his authorship of the notorious amendment – or the anti-Semitic content in his journalism – was discussed in the light of the blue plaque criterion that specified ‘a positive contribution to human welfare or happiness’. If he were considered by the panel today, it is likely that they would come to a different decision.

Labouchere’s plaque is on what is now Radnor House School, 19 Cross Deep, Twickenham. The sprawling riverside mansion was built in 1842−3 to designs by HE Kendall Junior, and was much rebuilt while Labouchere and his wife, Henrietta – a former actress and burlesque dancer – were in residence (1881–1903).

Known as Pope’s Villa, it lay near the site of the former residence of the poet Alexander Pope. The Laboucheres liked to pass off a bedroom at their house as being the poet’s own.

Further Reading

- William Fize, ‘The homosexual exception? The case of the Labouchère Amendment’, Cahiers Victorien et Édouardiens (2020) (accessed 11 August 2020)

- Claire Hirshfield, ‘Labouchere, truth and the uses of antisemitism’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 26:3 (1993), 134–42

- Herbert Sidebotham, ‘Henry Labouchere (1831–1912)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2009) (public library subscription required)