Setting up home

The two women met in Ireland in 1768 when Sarah was a teenager and Eleanor was in her late twenties. Both had been born into the Irish aristocracy, but were not prepared to follow the path that was expected of them, which typically involved being married off to an appropriate male suitor at a young age.

In 1778, when Sarah was 23 and Eleanor 39, they left Ireland together, much to the consternation of their families. They made their way to north Wales and for a while led a fairly nomadic life. Eventually they set up home in a modest stone-built cottage on the outskirts of the village of Llangollen, which they improved and converted into a Gothic fantasy home, filled with eclectic features from the medieval to the baroque. They renamed it Plas Newydd, meaning ‘the New House’ in Welsh.

Here Sarah and Eleanor lived in rural ‘retirement’, pursuing scholarly interests in the library they added to the house, farming on adjacent plots of land they acquired over time, and developing a carefully designed garden full of unusual Gothic features.

Celebrity status

The Ladies of Llangollen gained something of a celebrity status, fuelled by a mix of admiration for their independence, curiosity about their close companionship, and intrigue over their refusal to conform to social norms. They became symbols of female autonomy, inspiring discussions about women's roles, friendship, and love.

Welcoming guests to their home was central to their lives and they became renowned for their hospitality. Being located on the main route between London and Ireland meant that they received many passing callers. Distinguished visitors to Plas Newydd included the Duke of Wellington, Lord Byron, William Wordsworth and Charles Darwin. On the instruction of Queen Charlotte, George III gave them a royal pension, providing them with financial security in their later years.

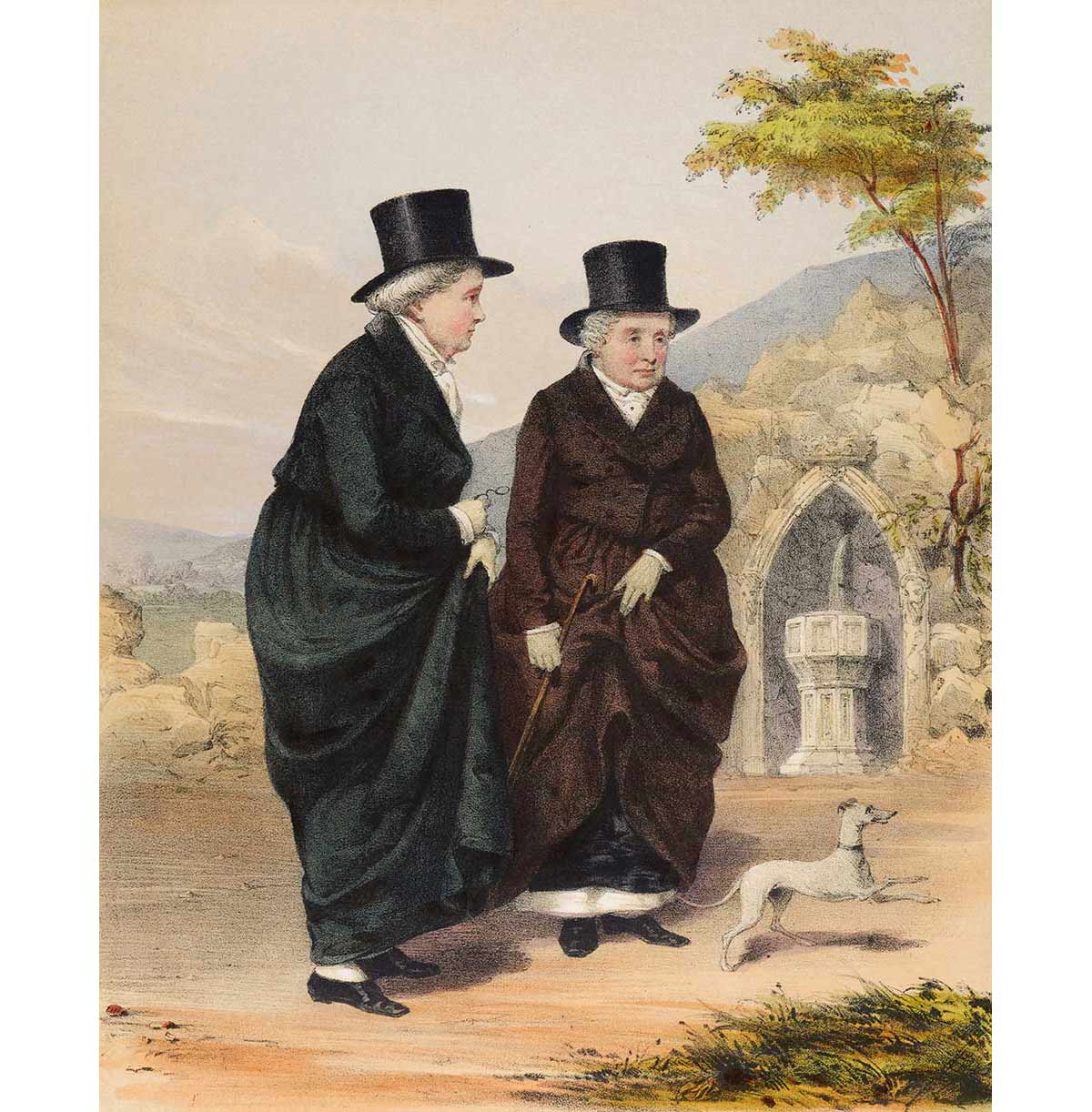

The ladies dressed in a manner which was seen as unconventional for women of their time, for example wearing riding habits with high-collared shirts, waistcoats and beaver hats. After their deaths, descriptions of their clothes became more exaggerated. Instead of being seen merely as part of their broader defiance of convention, their fashion choices were construed by some as being overtly ‘masculine’, perhaps with the intention of fuelling speculation about their sexuality.

Subsequently, the nature of the women’s relationship has been the subject of much debate. While we may never know whether their relationship was sexual, the existence of a loving bond between them is irrefutable.

Secret portraits

This was a time when portraits of celebrities, in the form of prints, were widely circulated and keenly collected, and the fame of the Ladies of Llangollen meant that there was demand for images of them. Sarah and Eleanor were reputedly reluctant to sit for their portraits, but some visitors still attempted to capture their likenesses.

Chief among them was Mary Parker (1799–1864), later Lady Leighton, whose family’s ancestral home, Sweeney Hall, was only 15 miles from Plas Newydd. Mary was an accomplished amateur artist and occasionally sent Sarah and Eleanor drawings of their gardens and the surrounding countryside. She appears to have been a frequent visitor, and on one occasion managed to surreptitiously sketch simple pencil portraits of the two women.

After the deaths of Eleanor in 1829 and Sarah in 1831, Mary Parker worked up her sketched portraits of the ladies into an imagined composition, in watercolour, showing them sitting in their library. She is believed to have gained access to Plas Newydd one final time before it was sold in 1832, to record the interior of the library for this purpose.

The resulting image was subsequently translated into print by the lithographer Richard James Lane (1800–72) – an impression of which can now be found in the Audley End collection. Around this time Lane was becoming well known for his lithographs of society figures and theatre personalities, so he was presumably seen as the perfect person to undertake this commission.

Popular prints

The widespread dissemination of Richard Lane’s print not only fuelled the Ladies of Llangollen’s celebrity status but also gave other printmakers the opportunity to pirate the image for their own financial gain.

One of the best-known examples of this is a lithograph produced by James Henry Lynch (active 1815–68). He replicated the portrait heads of the ladies, but transposed them into an outdoor setting and worked them into an entirely different composition. In a hand-coloured version of this print at Audley End, the ladies are depicted wearing riding habits and standing beside a medieval font, one of the most celebrated features in the garden at Plas Newydd.

Prints like these became popular among collectors and were valued not just for their subject matter but their relative rarity. Less refined derivatives were produced by other jobbing printmakers and are said to have been displayed at inns across Wales and sold to tourists.

Reaching Audley End

How the two lithographs ended up at Audley End is not documented, but a handwritten inscription on Lane’s helps to establish its provenance. A note at the top of the page reads: ‘With Lady Leighton’s compts [compliments] to Ld John Fitzroy’.

Lady Leighton was, of course, Mary Parker – the artist whose original portrait of the ladies in their library Lane’s lithograph reproduced. The inscription therefore tells us that Mary herself gave this copy of the print (an early and highly desirable ‘proof’ copy) to Lord John Fitzroy, who was an occasional visitor to Audley End during the 1840s.

At this time the house was owned by Richard Neville, 3rd Lord Braybrooke, and his wife, Jane. Lord Fitzroy was a Member of Parliament for Bury St Edmunds, near Culford Hall, where Jane, Lady Braybrooke, had grown up, and this seems to be the most likely source of the family connection.

Why Fitzroy decided to give a print of the Ladies of Llangollen to Lord and Lady Braybrooke at Audley End remains a mystery. But his gift reflects the fact that the ladies were still very much the subject of public fascination at the time he was visiting Audley End – so he may simply have been helping the family to fill a gap in their collection of ‘celebrity’ portraits.

The convoluted process through which the portraits of the Ladies of Llangollen appear to have ended up at Audley End reflects the interconnected world of aristocratic friendship, print collecting and gift exchange that existed during the period.

Moreover, the presence of the prints at Audley End demonstrates the enormous potential that these kinds of visual sources have for exploring the lives of individuals across time and place. It also helps us to understand why the printed likenesses of such unique and remarkable historical figures as Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby might have appealed to collectors such as Lord and Lady Braybrooke at Audley End.

By Dr Peter Moore, Curator of Collections and Interiors at Audley End

Further reading

The British Museum, The Ladies of Llangollen

Cadw, The Ladies of Llangollen

Sublime Wales, Ladies of Llangollen – portraits

Romilly’s Cambridge Diary, 1842–1847, edited by ME Bury and JD Pickles (Cambridge, 1994)

Find out more

-

VISIT AUDLEY END

Explore an English country house upstairs and downstairs, inside and out.

-

HISTORY OF AUDLEY END

Read a full account of Audley End’s long and varied history, from the priory founded on the site in the 12th century to the present day.

-

Collection Highlights

View detailed images of some highlights from the diverse collection at Audley End – from paintings to natural history tableaux.

-

LGBTQ+ History

Find out about the lives of some LGBTQ+ individuals and their place in the stories of English Heritage sites.