The Norman castle

As part of his campaign to establish control across the country, in 1068 William the Conqueror captured Exeter after a siege. He entrusted the city to the Norman commander Baldwin of Meulles, appointing him sheriff of Devon.

Baldwin was one of many Norman aristocrats who replaced English lords and controlled the conquered country for William. He supervised the construction of the royal castle at Exeter.

At some point between 1068 and 1086 Baldwin built his own castle on one of his newly granted estates outside the village of Okehampton, 25 miles from Exeter. By digging three ditches across a spur of high ground beside the West Okement river and piling up the spoil, he created the classic symbol of Norman military might, an earthen motte or mound. The river and a tributary stream acted as a moat on two sides of the castle and there were two outer courtyards (or baileys), one on either side of the motte.

To complete the castle, either Baldwin or his son Richard (d.1137) added a stone tower on top of the motte. We don’t know how many buildings this early castle had: excavation of the east bailey failed to find any Norman buildings.

The castle in the 13th century

A century later another family of Norman aristocrats acquired the castle, when Reginald Courtenay (d.1190) married Baldwin’s great-great-niece Hawisia. The Courtenays were to hold the castle for nearly four centuries.

In 1178 Reginald paid for a papal licence to have a private chapel here, and it may have been soon after this that he started to build at his new castle. Archaeological evidence shows that he and his son Robert (d.1242) rebuilt the east bailey in stone, adding a new gatehouse and a range of buildings along the north side.

But by 1274 the site was described in a survey as ‘an old motte that is worth nothing and there is in the same place, beyond the aforesaid motte, a certain hall, chamber and kitchen in poor repair’.

It wasn’t until the early 14th century that the castle we see today took shape. It was built by a great-great grandson of Reginald, Hugh Courtenay II (1276–1340), who inherited the barony of Okehampton – including its castle – in 1292.

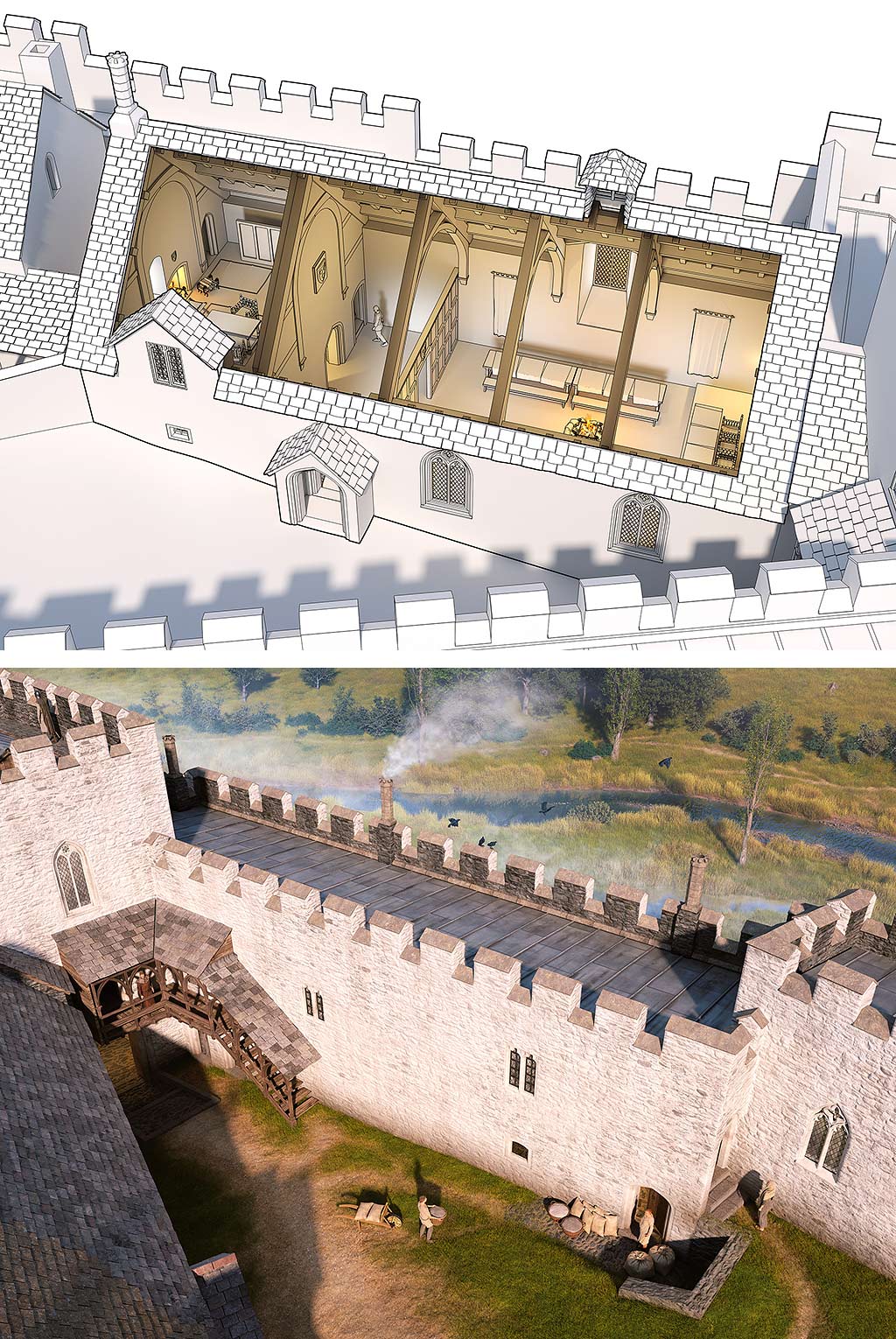

Move the sliding bar to compare two reconstruction views showing how the castle may have looked in about 1100 (left) and about 1400 (right), following rebuilding works in the 14th century. © Historic England (illustrations by Josep R Casals)

Hugh Courtenay’s castle

Hugh came of age in 1297 and joined Edward I’s invading army in Scotland, taking part in many campaigns there until 1308. He was knighted in about 1298 and the following year was summoned to Parliament as Lord Courtenay. In the first decade of the 14th century Hugh, along with his mother, Eleanor, and his wife, Agnes, set about rebuilding their castles at Tiverton and Okehampton.

At Okehampton the Courtenays doubled the footprint of the Norman keep, changing it from a tower into a mansion, and repaired the 13th-century bailey walls and gatehouse. They added an outer gatehouse with a walled passageway that led to the old gatehouse.

Inside the bailey they built a new hall where they dined on important occasions, and where their tenant farmers came to pay their fees and agree tenancies.

Beyond the hall was a detached kitchen with three separate rooms – one for roasting meats and boiling pottage, the second for storage and preparation and the third for baking bread and pies.

Hugh also upgraded the accommodation at Okehampton, building a new lodging suite by the gatehouse. All three upper rooms had the medieval luxuries of a private lavatory, a fireplace and a window-seat, as did the new rooms in the old keep. The window-seats offered views of the hunting in the deer park which Hugh’s mother and father had set up on the other side of the valley.

The Courtenays also rebuilt the chapel, some of whose walls survive almost to roof height.

The Courtenay Earls of Devon

Hugh had inherited the earldom of Devon in 1293 through his great-grandmother Mary de Redvers, after the death of the last Redvers heir, Isabella de Fortibus. But it was not until 1335 that he finally gained the formal title Earl of Devon. His great-grandson Edward Courtenay (1357–1419), the 3rd Earl, commissioned a family tree in the early 15th century, which illustrates Edward’s glorious ancestors, beginning with the Norman knight Baldwin of Meulles in the 11th century and continuing with later family members such as Robert Courtenay and the castle-building Hugh Courtenay.

But disaster was soon to strike the family. The heroic Courtenays of the 11th to 14th centuries were succeeded by a generation killed or executed during the 15th-century Wars of the Roses, which were fought between rival factions for the throne of England. Between 1461 and 1471 the three male Courtenay heirs lost their lives, having chosen the losing side of the Lancastrian Henry VI. The last medieval Earl of Devon, John Courtenay, died on the battlefield at Tewkesbury in 1471.

Royal confiscation

In 1511 the young Henry VIII regranted the title Earl of Devon to distant cousins of John Courtenay. The third of the new earls was Henry Courtenay (1498–1538), Henry VIII’s cousin, friend and hunting companion.

But by the 1530s Henry Courtenay was at odds with the king’s new policies on religion. Like many in Devon, he favoured traditional religion and opposed the closure of monasteries.

In 1538 news reached Henry VIII of an ‘Exeter Conspiracy’, in which Courtenay and another of the king’s cousins, Reginald Pole, were supposedly conspiring to revolt and overthrow him. Courtenay was quickly arrested, tried for treason and beheaded at the Tower of London in December 1538. The Crown seized most of Henry Courtenay’s lands and castles and the Courtenay earldom was no more.

16th- and 17th-century decay

In 1544 Henry VIII leased and then granted Okehampton’s hunting park to Sir Peter Carew (c.1514–75), a charismatic Anglo-Irish soldier and distant relative of the Courtenays.

Although he did not own the castle itself, it was probably Carew who began stripping it of materials of value, perhaps to pay his large debts (indeed, he paid little attention to legal niceties of ownership, seizing Dartmouth Castle a few years later). Archaeological evidence shows that items such as the Beer stone columns supporting the gatehouse were removed at this time. With their roofs stripped of lead, the castle buildings must have quickly deteriorated.

Okehampton Castle – unlike many medieval castles – was not pressed into use in the Civil Wars of the 1640s. But the castle did see a renewed use in 1683, when John Ellacot, future mayor of Okehampton, and his wife Tamsin seem to have set up a bakehouse there. Their lease refers to the castle gatehouse – part of which they may have occupied – and ‘all the rooms’ within the ‘old decayed castle’. They built an oven in the medieval western lodging in the bailey. They also seem to have refurbished the castle chapel and priest’s lodging, and laid out a small garden within the bailey.

Romantic ruin

By the 18th century the castle’s medieval ruins had acquired a cultural and aesthetic value, evoking a glorious English past. And so, like many old castles and abbeys, Okehampton began to attract artists. From the 1720s Samuel and Nathaniel Buck began publishing printed views of English towns and antiquities and in 1734 they were in Devon, drawing the castles at Tiverton, Berry Pomeroy and Okehampton.

Eighty years later, in 1814, JMW Turner sketched the castle during his tour of England, and he later painted it.

The Okehampton ghost song

An old Devon ghost song, ‘My Lady’s Coach’, recounts the story of an ‘ashen white’ woman who travels in a silent coach and horses driven by a headless driver, picking up – and killing – passengers along the way:

My Ladye hath a sable coach

And horses two and four.

My Ladye hath a gaunt blood-hound

That runneth on before.

My Ladye’s Coach hath nodding plumes,

The driver hath no head.

My Ladye is an ashen white,

As one that long is dead.

Locals told a 19th-century folk song collector, Sabine Baring-Gould, that the song was about a Lady Howard, who journeyed nightly in her ghostly coach from Okehampton Castle to Launceston Castle (or in another version, from Tavistock to Okehampton).

This ‘Lady Howard’ is probably based on Mary Fitz (1596–1671), the daughter of Sir John Fitz of Tiverton and Lady Bridget Courtenay of Powderham. Mary’s father was a violent drinker who committed two or three murders, banished his wife and child from his home, and killed himself. Mary married four times. Her first three husbands all died, and after the death of the third, Sir Charles Howard (hence her title), she married Sir Richard Grenville. With some scandal, she then divorced the violent Sir Richard and fell out with their two children.

With this colourful family history and the connection to the Courtenays, it is easy to see how a ghost song about death and penance became associated with both Mary Fitz and Okehampton Castle.

More about the ghost songConservation and excavation

By the early 20th century the castle ruins were largely obscured by ivy and trees. Sydney Simmons, a local businessman, bought the castle site in 1911 and paid for ivy to be cleared and the ruined walls stabilised. In 1917 he gave the restored castle to the newly formed Okehampton Castle Trust, who employed a custodian and produced the first guide and map.

By the 1960s the trust was struggling to meet the costs of maintaining a ruined castle, and in 1967 it donated the castle to the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works. In 1972 Robert Higham of the University of Exeter began a programme of archaeological excavation and research. Since 1984 the castle ruins have been in the care of English Heritage.

The Courtenay bells

Two fine medieval copper-alloy bells probably made for Okehampton Castle are now displayed in the Museum of Dartmoor Life in Okehampton.

Like many medieval bells, each has an inscription that was part of the original design, stamped into the mould that cast the bells. One reads: WE BEUT IMAKID BOTHE TOWAKIE ELIANORE FOR TO KACHE GAME (‘We beat, both made to wake Eleanor to catch game’). The other reads: HAC DO BIMIREREDE THENK ONHUUSSOULE ANC SOWAS HISNAME (‘Listen: do, by my advice, think about whose [Hugh’s] soul – and so was his name’).

The inscriptions suggest that the bells were cast for Lady Eleanor Courtenay, widow of Hugh Courtenay I, after the Okehampton deer park was laid out soon after 1306 and before Eleanor’s death in 1328. Was this part of a family joke after a morning lie-in and a late hunting trip?

The bells probably hung in the wall tower next to the castle chapel and could be rung for both Mass and hunting trips.

Image: One of the 14th-century bells that probably hung in the castle chapel

Further reading

S Baring-Gould, Devonshire Characters and Strange Events (London, 1908) [history of ‘Lady Howard’ and the Okehampton folk song, 194–211]

Courtenay Archive, University of Exeter [medieval family tree]

O Creighton, ‘Room with a view: framing castle landscapes’, Château Gaillard, 24 (2010), 37–49 [discusses relationship of castle and deer park]

O Creighton and RA Higham, ‘Form, function and fluidity in castles: water and fortification in medieval Britain’, in Rethinking Medieval Ireland and Beyond: Lifecycles, Landscapes, and Settlements, eds VL McAlister and L Shine (Leiden, 2022), 75–106 [discusses water management at Okehampton Castle]

RA Higham, ‘Excavations at Okehampton Castle, Devon, Part 1: The motte and keep’, Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological and Natural History Society, 35 (1977), 3–42

RA Higham, J Allen and SR Blaylock, ‘Excavations at Okehampton Castle, Devon, Part 2: The bailey’, Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological and Natural History Society, 40 (1982), 19–151

S Probert, ‘Okehampton Castle and Park, West Devon: survey report’ (English Heritage, Swindon, 2004) [earthworks survey of castle and deer park]

JB Rowe, ‘Ninth report of the Committee on Devonshire Records’, Transactions of the Devonshire Association, 31 (1899), 120–45 [Ellacot’s lease of 1683, 135] (accessed 16 Dec 2024)

EH Young, Okehampton, Parochial Histories of Devonshire (Exeter, 1931) [prints original sources relating to town and castle]

Find out more

-

Visit Okehampton Castle

Devon’s biggest and most picturesque castle

-

Buy the guidebook

This guidebook tells the story of the castle with the aid of atmospheric photography and stunning reconstruction drawings.

-

Isabella De Fortibus

Countess Isabella de Fortibus was one of the greatest heiresses in 13th-century England. Her life story illustrates how powerful women of noble birth could become in the Middle Ages.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.