The forgotten frontier

The Roman army advanced through northern England and into Scotland in the AD 80s while attempting to conquer Britain. Uprisings elsewhere in the empire meant that the army then retreated to a frontier across the narrowest part of northern England – the Tyne–Solway isthmus.

Under the emperor Trajan (r.AD 98–117), the frontier consisted of a system of fortifications on or near a road now known as the Stanegate, which ran east–west between Corbridge and Carlisle. Several large forts, such as Vindolanda, and smaller fortlets were built along the road. These were bases for Roman military operations along the northern border of the province of Britannia, and homes to the soldiers who protected Britannia from hostile tribes in the north.

Pike Hill was one of various signal towers that stood on high ground usually to the north of the Stanegate. It offered commanding views in all directions, allowing the small garrison to monitor the landscape. They could signal to the nearest forts at Nether Denton (1¼ miles away) and Castle Hill, Boothby (2½ miles away), where larger forces of up to 1,000 soldiers could respond to any threats.

Then in the AD 120s the situation changed when the new emperor, Hadrian (r.117–38), completely reshaped the borders of the Roman Empire.

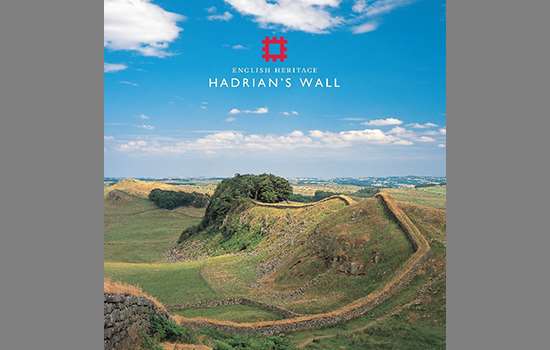

Hadrian’s Wall

Construction started on Hadrian’s Wall around AD 122, as part of Hadrian’s strategy of strengthening the north-west frontiers of the empire. Typically, Roman frontiers, such as the system around the Stanegate, consisted of large military bases and smaller outposts at important locations, joined by roads to allow swift communications. The landscape was monitored but not closed off to all travel. Smuggling or small-scale raiding was still feasible in bad weather or at night, although larger attacks could be dealt with by the garrisons stationed at the forts.

Hadrian, however, ordered the construction of a continuous wall and V-shaped ditch north of the Stanegate, running 80 Roman miles (73 miles) from Wallsend on the eastern coast to Burgh-by-Sands on the Solway Firth. This effectively closed the frontier, preventing uninhibited and unmonitored access to the province. The western end of the Wall (the 30 or so miles west of the river Irthing) was initially built of turf, but was replaced in stone later in Hadrian’s reign.

The Wall was heavily fortified with military installations roughly every 500 metres along its length. Small forts, known as milecastles, were spaced about a Roman mile apart, and housed garrisons of up to about 30 soldiers. Positioned at equal distances between each pair of milecastles were two turrets, providing further vantage points from which to monitor the landscape.

Pike Hill and the Wall

Standing on the higher ground north of the Stanegate, Pike Hill was already on the intended route of the Wall, and was incorporated within it.

Originally, it seems that the plan was for the Wall and its small garrisons to work together with the soldiers stationed in forts on the Stanegate. The soldiers at Pike Hill would therefore monitor the landscape and communicate with the forts on the Stanegate as they had done before. But after work on the Wall started, large forts such as Birdoswald were added to its line, to house large garrisons of soldiers and respond to emergencies.

Pike Hill still had a role to play, however, since its location meant it could relay messages from Castlesteads fort to the east to the new fort of Birdoswald to the west. Roman objects found in the tower suggest that it remained in use by soldiers until the later 4th century AD.

Signalling on Hadrian’s Wall

Both before and after Hadrian’s Wall was built, signalling appears to have been the primary purpose of Pike Hill. Although no direct evidence of how the Romans communicated on Hadrian’s Wall has been found, accounts by Roman authors, archaeological evidence from elsewhere in the empire, and the positioning of Pike Hill provide clues as to how messages might have been transmitted.

Everyday communications along Hadrian’s Wall, such as orders, would have been conveyed by messengers, probably on horseback. But the Romans required methods to communicate quickly and visually over large distances. The simplest and most reliable method to transmit a simple, urgent message was fire, either via a lit torch or a pre-prepared beacon. These could be lit and understood with no specialist skills.

For this method to work, positioning was crucial. Many of the towers and milecastles on Hadrian’s Wall appear to have be positioned with clear views to the south.

The Tower’s Remains

Pike Hill takes advantage of the views from the highest point in the area, with clear lines of sight to the nearest forts on the Wall and the Stanegate. Much of the tower was destroyed in 1870 when a cutting was made for the road beside it, but parts of two sides and one corner survive.

While turrets were built in line with the Wall, Pike Hill lay at an angle to it: the Wall was attached to the tower at an angle of about 45 degrees, and the ditch had to zigzag to pass around it to the north.

Internally the tower was 6.10 metres square, and the masonry was finished to a much higher standard than that of the adjacent turrets of Hadrian’s Wall. Like all the installations of the Wall, the upper sections of the tower’s walls do not survive, but it is likely that there was a least one further storey, giving access to the walkway that presumably ran along the top of the Wall. Above that, it had either an open platform or a roof.

Excavations in the 1930s revealed evidence of a hearth in the tower’s surviving south-east corner, which would have been used for cooking and for keeping warm, and a door at ground level.

In turrets elsewhere along Hadrian’s Wall, items such as gaming counters and cooking utensils have been found, showing that they provided shelter where small groups of soldiers could cook, sleep and relax during their periods of watch and patrol on the Wall.

A broken stone slab, inscribed with part of the name of the emperor Antoninus Pius (r.AD 138–61), was found here in 1862. It may have been a record of repairs to the tower conducted during his reign and proudly displayed on its walls.

Hadrian’s Wall in the area

Pike Hill is one of several Hadrian’s Wall sites west of Birdoswald Roman Fort, including Banks East Turret and Hare Hill to the west of Pike Hill, and Leahill and Piper Sike turrets to the east.

Birdoswald itself lies at the western end of a particularly spectacular stretch of Wall which includes Harrows Scar Milecastle, Poltross Burn Milecastle and Turrets, and Willowford Wall, Bridge and Turrets.

More about Hadrian’s Wall

-

Hadrian’s Wall: History and Stories

Discover the history and stories associated with Hadrian’s Wall, the north-western frontier of the Roman Empire.

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

-

Buy the guidebook to Hadrian’s Wall

The English Heritage guidebook to the Wall provides maps, plans and tours of all the key sites, as well as a history of the Wall and its forts.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.